Key Judgements: Iraq's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs

Discussion: Iraq's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs

UN Security Council Resolutions and Provisions

for Inspections and Monitoring: Theory and Practice

The Central Intelligence Agency,

United States of America

Iraq has continued its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs in defiance of UN resolutions and restrictions. Baghdad has chemical and biological weapons as well as missiles with ranges in excess of UN restrictions; if left unchecked, it probably will have a nuclear weapon during this decade.

Baghdad hides large portions of Iraq's WMD efforts. Revelations after the Gulf war starkly demonstrate the extensive efforts undertaken by Iraq to deny information.

Since inspections ended in 1998, Iraq has maintained its chemical weapons effort, energized its missile program, and invested more heavily in biological weapons; most analysts assess Iraq is reconstituting its nuclear weapons program.

How quickly Iraq will obtain its first nuclear weapon depends on when it acquires sufficient weapons-grade fissile material.

Baghdad has begun renewed production of chemical warfare agents, probably including mustard, sarin, cyclosarin, and VX. Its capability was reduced during the UNSCOM inspections and is probably more limited now than it was at the time of the Gulf war, although VX production and agent storage life probably have been improved.

All key aspects—R&D, production, and weaponization—of Iraq's offensive BW program are active and most elements are larger and more advanced than they were before the Gulf war.

Iraq maintains a small missile force and several development programs, including for a UAV that most analysts believe probably is intended to deliver biological warfare agents.

In April 1991, the UN Security Council enacted Resolution 687 requiring Iraq to declare, destroy, or render harmless its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) arsenal and production infrastructure under UN or International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) supervision. UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 687 also demanded that Iraq forgo the future development or acquisition of WMD.

Baghdad's determination to hold onto a sizeable remnant of its WMD arsenal, agents, equipment, and expertise has led to years of dissembling and obstruction of UN inspections. Elite Iraqi security services orchestrated an extensive concealment and deception campaign to hide incriminating documents and material that precluded resolution of key issues pertaining to its WMD programs.

Successive Iraqi declarations on Baghdad's pre-Gulf war WMD programs gradually became more accurate between 1991 and 1998, but only because of sustained pressure from UN sanctions, Coalition military force, and vigorous and robust inspections facilitated by information from cooperative countries. Nevertheless, Iraq never has fully accounted for major gaps and inconsistencies in its declarations and has provided no credible proof that it has completely destroyed its weapons stockpiles and production infrastructure.

| Resolution Requirement | Reality |

| Res. 687 (3 April 1991) Requires Iraq to declare, destroy, remove, or render harmless under UN or IAEA supervision and not to use, develop, construct, or acquire all chemical and biological weapons, all ballistic missiles with ranges greater than 150 km, and all nuclear weapons-usable material, including related material, equipment, and facilities. The resolution also formed the Special Commission and authorized the IAEA to carry out immediate on-site inspections of WMD-related facilities based on Iraq's declarations and UNSCOM's designation of any additional locations. | Baghdad refused to declare all parts of each WMD program, submitted several declarations as part of its aggressive efforts to deny and deceive inspectors, and ensured that certain elements of the program would remain concealed. The prohibition against developing delivery platforms with ranges greater than 150 km allowed Baghdad to research and develop shorter-range systems with applications for longer-range systems and did not affect Iraqi efforts to convert full-size aircraft into unmanned aerial vehicles as potential WMD delivery systems with ranges far beyond 150 km. |

| Res. 707 (15 August 1991) Requires Iraq to allow UN and IAEA inspectors immediate and unrestricted access to any site they wish to inspect. Demands Iraq provide full, final, and complete disclosure of all aspects of its WMD programs; cease immediately any attempt to conceal, move, or destroy WMD-related material or equipment; allow UNSCOM and IAEA teams to use fixed-wing and helicopter flights throughout Iraq; and respond fully, completely, and promptly to any Special Commission questions or requests. | Baghdad in 1996 negotiated with UNSCOM Executive Chairman Ekeus modalities that it used to delay inspections, to restrict to four the number of inspectors allowed into any site Baghdad declared as "sensitive," and to prohibit them altogether from sites regarded as sovereign. These modalities gave Iraq leverage over individual inspections. Iraq eventually allowed larger numbers of inspectors into such sites but only after lengthy negotiations at each site. |

| Res. 715 (11 October 1991) Requires Iraq to submit to UNSCOM and IAEA long-term monitoring of Iraqi WMD programs; approved detailed plans called for in UNSCRs 687 and 707 for long-term monitoring. | Iraq generally accommodated UN monitors at declared sites but occasionally obstructed access and manipulated monitoring cameras. UNSCOM and IAEA monitoring of Iraq's WMD programs does not have a specified end date under current UN resolutions. |

| Res. 1051 (27 March 1996) Established the Iraqi export/import monitoring system, requiring UN members to provide IAEA and UNSCOM with information on materials exported to Iraq that may be applicable to WMD production, and requiring Iraq to report imports of all dual-use items. | Iraq is negotiating contracts for procuring—outside of UN controls—dual-use items with WMD applications. The UN lacks the staff needed to conduct thorough inspections of goods at Iraq's borders and to monitor imports inside Iraq. |

| Res. 1060 (12 June 1996) and Resolutions 1115, 1134, 1137, 1154, 1194, and 1205. Demands that Iraq cooperate with UNSCOM and allow inspection teams immediate, unconditional, and unrestricted access to facilities for inspection and access to Iraqi officials for interviews. UNSCR 1137 condemns Baghdad's refusal to allow entry to Iraq to UNSCOM officials on the grounds of their nationality and its threats to the safety of UN reconnaissance aircraft. | Baghdad consistently sought to impede and limit UNSCOM's mission in Iraq by blocking access to numerous facilities throughout the inspection process, often sanitizing sites before the arrival of inspectors and routinely attempting to deny inspectors access to requested sites and individuals. At times, Baghdad would promise compliance to avoid consequences, only to renege later. |

| Res. 1154 (2 March 1998) Demands that Iraq comply with UNSCOM and IAEA inspections and endorses the Secretary General's memorandum of understanding with Iraq, providing for "severest consequences" if Iraq fails to comply. Res. 1194 (9 September 1998) Condemns Iraq's decision to suspend cooperation with UNSCOM and the IAEA. Res. 1205 (5 November 1998) Condemns Iraq's decision to cease cooperation with UNSCOM. | UNSCOM could not exercise its mandate without Iraqi compliance. Baghdad refused to work with UNSCOM and instead negotiated with the Secretary General, whom it believed would be more sympathetic to Iraq's needs. |

| Res. 1284 (17 December 1999) Established the United Nations Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC), replacing UNSCOM; and demanded that Iraq allow UNMOVIC teams immediate, unconditional, and unrestricted access to any and all aspects of Iraq's WMD program. | Iraq repeatedly has rejected the return of UN arms inspectors and claims that it has satisfied all UN resolutions relevant to disarmament. Compared with UNSCOM, 1284 gives the UNMOVIC chairman less authority, gives the Security Council a greater role in defining key disarmament tasks, and requires that inspectors be full-time UN employees. |

Since December 1998, Baghdad has refused to allow UN inspectors into Iraq as required by the Security Council resolutions. Technical monitoring systems installed by the UN at known and suspected WMD and missile facilities in Iraq no longer operate. Baghdad prohibits Security Council-mandated monitoring overflights of Iraqi facilities by UN aircraft and helicopters. Similarly, Iraq has curtailed most IAEA inspections since 1998, allowing the IAEA to visit annually only a very small number of sites to safeguard Iraq's stockpile of uranium oxide.

In the absence of inspectors, Baghdad's already considerable ability to work on prohibited programs without risk of discovery has increased, and there is substantial evidence that Iraq is reconstituting prohibited programs. Baghdad's vigorous concealment efforts have meant that specific information on many aspects of Iraq's WMD programs is yet to be uncovered. Revelations after the Gulf war starkly demonstrate the extensive efforts undertaken by Iraq to deny information.

More than ten years of sanctions and the loss of much of Iraq's physical nuclear infrastructure under IAEA oversight have not diminished Saddam's interest in acquiring or developing nuclear weapons.

Iraq had an advanced nuclear weapons development program before the Gulf war that focused on building an implosion-type weapon using highly enriched uranium. Baghdad was attempting a variety of uranium enrichment techniques, the most successful of which were the electromagnetic isotope separation (EMIS) and gas centrifuge programs. After its invasion of Kuwait, Iraq initiated a crash program to divert IAEA-safeguarded, highly enriched uranium from its Soviet and French-supplied reactors,but the onset of hostilities ended this effort. Iraqi declarations and the UNSCOM/IAEA inspection process revealed much of Iraq's nuclear weapons efforts, but Baghdad still has not provided complete information on all aspects of its nuclear weapons program.

Before its departure from Iraq, the IAEA made significant strides toward dismantling Iraq's nuclear weapons program and unearthing the nature and scope of Iraq's past nuclear activities. In the absence of inspections, however, most analysts assess that Iraq is reconstituting its nuclear program—unraveling the IAEA's hard-earned accomplishments.

Iraq retains its cadre of nuclear scientists and technicians, its program documentation, and sufficient dual-use manufacturing capabilities to support a reconstituted nuclear weapons program. Iraqi media have reported numerous meetings between Saddam and nuclear scientists over the past two years, signaling Baghdad's continued interest in reviving a nuclear program.

Iraq's expanding international trade provides growing access to nuclear-related technology and materials and potential access to foreign nuclear expertise. An increase in dual-use procurement activity in recent years may be supporting a reconstituted nuclear weapons program.

Baghdad may have acquired uranium enrichment capabilities that could shorten substantially the amount of time necessary to make a nuclear weapon.

Iraq has the ability to produce chemical warfare (CW) agents within its chemical industry, although it probably depends on external sources for some precursors. Baghdad is expanding its infrastructure, under cover of civilian industries, that it could use to advance its CW agent production capability. During the 1980s Saddam had a formidable CW capability that he used against Iranians and against Iraq's Kurdish population. Iraqi forces killed or injured more than 20,000 people in multiple attacks, delivering chemical agents (including mustard agent[1] and the nerve agents sarin and tabun[2]) in aerial bombs, 122mm rockets, and artillery shells against both tactical military targets and segments of Iraq's Kurdish population. Before the 1991 Gulf war, Baghdad had a large stockpile of chemical munitions and a robust indigenous production capacity.

| Documented Iraqi Use of Chemical Weapons | ||||

| Date | Area Used | Type of Agent | Approximate Casualties | Target Population |

| Aug 1983 | Hajj Umran | Mustard | fewer than 100 | Iranians/Kurds |

| Oct-Nov 1983 | Panjwin | Mustard | 3,000 | Iranian/Kurds |

| Feb-Mar 1984 | Majnoon Island |

Mustard | 2,500 | Iranians |

|

Mar 1984 | al-Basrah | Tabun | 50 to 100 | Iranians |

| Mar 1985 | Hawizah Marsh | Mustard/Tabun | 3,000 | Iranians |

| Feb 1986 | al-Faw | Mustard/Tabun | 8,000 to 10,000 | Iranians |

| Dec 1986 | Umm ar Rasas | Mustard | thousands | Iranians |

| Apr 1987 | al-Basrah | Mustard/Tabun | 5,000 | Iranians |

| Oct 1987 | Sumar/Mehran | Mustard/nerve agents | 3,000 | Iranians |

| Mar 1988 | Halabjah | Mustard/nerve agents | hundreds | Iranians/Kurds |

Although precise information is lacking, human rights organizations have received plausible accounts from Kurdish villagers of even more Iraqi chemical attacks against civilians in the 1987 to 1988 time frame—with some attacks as late as October 1988—in areas close to the Iranian and Turkish borders.

More than 10 years after the Gulf war, gaps in Iraqi accounting and current production capabilities strongly suggest that Iraq maintains a stockpile of chemical agents, probably VX,[3] sarin, cyclosarin,[4] and mustard.

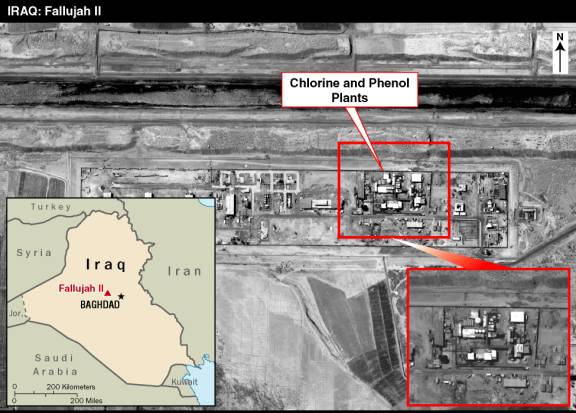

Baghdad continues to rebuild and expand dual-use infrastructure that it could divert quickly to CW production. The best examples are the chlorine and phenol plants at the Fallujah II facility. Both chemicals have legitimate civilian uses but also are raw materials for the synthesis of precursor chemicals used to produce blister and nerve agents. Iraq has three other chlorine plants that have much higher capacity for civilian production; these plants and Iraqi imports are more than sufficient to meet Iraq's civilian needs for water treatment. Of the 15 million kg of chlorine imported under the UN Oil-for-Food Program since 1997, Baghdad used only 10 million kg and has 5 million kg in stock, suggesting that some domestically produced chlorine has been diverted to such proscribed activities as CW agent production.

Iraq has the capability to convert quickly legitimate vaccine and biopesticide plants to biological warfare (BW) production and already may have done so. This capability is particularly troublesome because Iraq has a record of concealing its BW activities and lying about the existence of its offensive BW program.

After four years of claiming that they had conducted only "small-scale, defensive" research, Iraqi officials finally admitted to inspectors in 1995 to production and weaponization of biological agents. The Iraqis admitted this only after being faced with evidence of their procurement of a large volume of growth media and the defection of Husayn Kamil, former director of Iraq's military industries.

| Iraqi-Acknowledged Open-Air Testing of Biological Weapons | ||

| Location-Date | Agent | Munition |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Mar 1988 | Bacillus subtilis[5] | 250-gauge bomb (cap. 65 liters) |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Mar 1988 | Botulinum toxin | 250-gauge bomb (cap. 65 liters) |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Nov 1989 | Bacillus subtilis | 122mm rocket (cap. 8 liters) |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Nov 1989 | Botulinum toxin | 122mm rocket (cap. 8 liters) |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Nov 1989 | Aflatoxin | 122mm rocket (cap. 8 liters) |

| Khan Bani Saad – Aug 1988 | Bacillus subtilis | aerosol generator – Mi-2 helicopter with modified agricultural spray equipment |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Dec 1989 | Bacillus subtilis | R-400 bomb (cap. 85 liters) |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Nov 1989 | Botulinum toxin | R-400 bomb (cap. 85 liters) |

| Al Muhammadiyat – Nov 1989 | Aflatoxin | R-400 bomb (cap. 85 liters) |

| Jurf al-Sakr Firing Range – Sep 1989 | Ricin | 155mm artillery shell (cap. 3 liters) |

| Abu Obeydi Airfield – Dec 1990 | Water | Modified Mirage F1 drop-tank (cap. 2,200 liters) |

| Abu Obeydi Airfield – Dec 1990 |

Water/potassium permanganate | Modified Mirage F1 drop-tank (cap. 2,200 liters) |

| Abu Obeydi Airfield – Jan 1991 | Water/glycerine | Modified Mirage F1 drop-tank (cap. 2,200 liters) |

| Abu Obeydi Airfield – Jan 1991 | Bacillus subtilis/Glycerine | Modified Mirage F1 drop-tank (cap. 2,200 liters) |

Baghdad did not provide persuasive evidence to support its claims that it unilaterally destroyed its BW agents and munitions. Experts from UNSCOM assessed that Baghdad's declarations vastly understated the production of biological agents and estimated that Iraq actually produced two-to-four times the amount of agent that it acknowledged producing, including Bacillus anthracis—the causative agent of anthrax—and botulinum toxin.

The improvement or expansion of a number of nominally "civilian" facilities that were directly associated with biological weapons indicates that key aspects of Iraq's offensive BW program are active and most elements more advanced and larger than before the 1990-1991 Gulf war.

In addition to questions about activity at known facilities, there are compelling reasons to be concerned about BW activity at other sites and in mobile production units and laboratories. Baghdad has pursued a mobile BW research and production capability to better conceal its program.

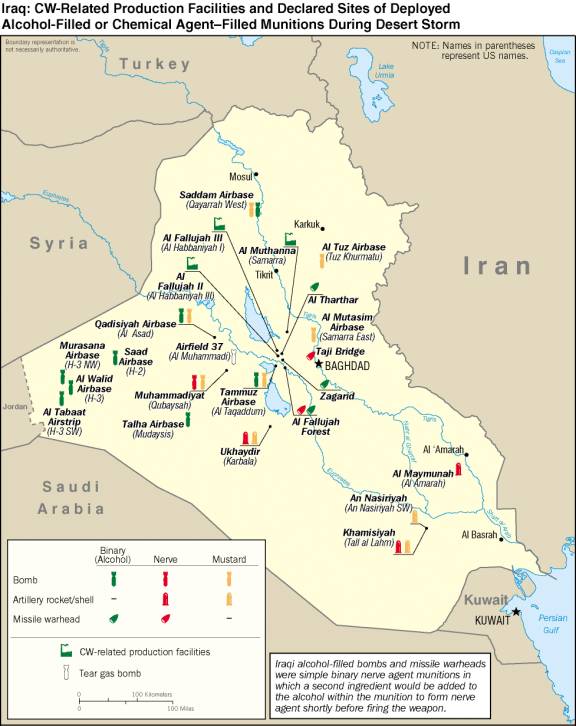

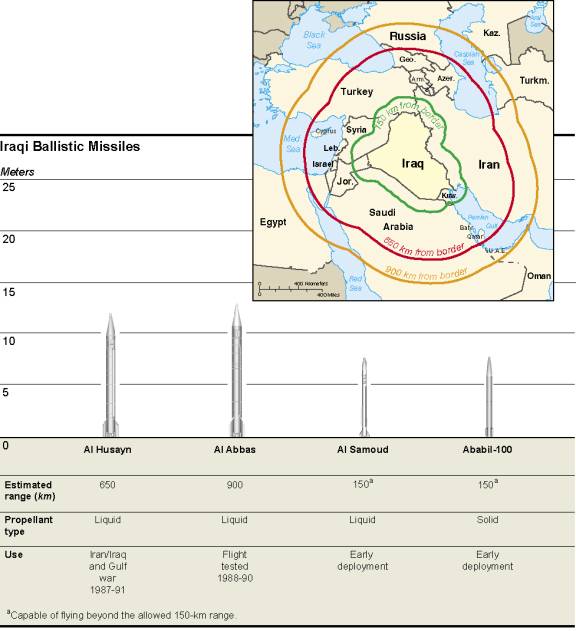

Iraq has developed a ballistic missile capability that exceeds the 150km range limitation established under UNSCR 687. During the 1980s, Iraq purchased 819 Scud B missiles from the USSR. Hundreds of these 300km range missiles were used to attack Iranian cities during the Iran-Iraq War. Beginning in 1987, Iraq converted many of these Soviet Scuds into extended-range variants, some of which were fired at Tehran; some were launched during the Gulf war, and others remained in Iraq's inventory at war's end. Iraq admitted filling at least 75 of its Scud warheads with chemical or biological agents and deployed these weapons for use against Coalition forces and regional opponents, including Israel in 1991.

Most of the approximately 90 Scud-type missiles Saddam fired at Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain during the Gulf war were al-Husayn variants that the Iraqis modified by lengthening the airframe and increasing fuel capacity, extending the range to 650 km.

Baghdad was developing other longer-range missiles based on Scud technology, including the 900km al-Abbas. Iraq was designing follow-on multi-stage and clustered medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) concepts with intended ranges up to 3,000 km. Iraq also had a program to develop a two-stage missile, called the Badr-2000, using solid-propellants with an estimated range of 750 to 1,000 km.

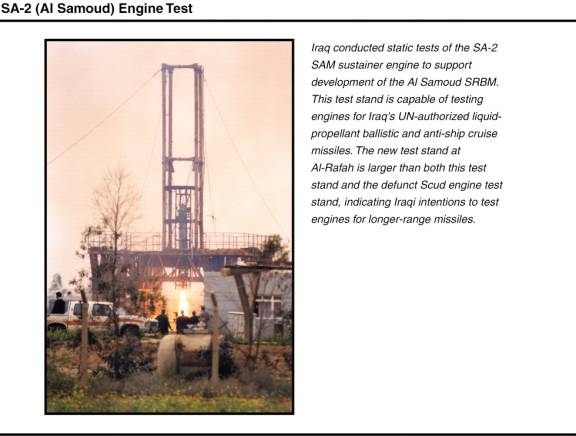

Iraq continues to work on UN-authorized short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs)—those with a range no greater than 150 km—that help develop the expertise and infrastructure needed to produce longer-range missile systems. The al-Samoud liquid propellant SRBM and the Ababil-100 solid propellant SRBM, however, are capable of flying beyond the allowed 150km range. Both missiles have been tested aggressively and are in early deployment. Other evidence strongly suggests Iraq is modifying missile testing and production facilities to produce even longer-range missiles.

Iraq has managed to rebuild and expand its missile development infrastructure under sanctions. Iraqi intermediaries have sought production technology, machine tools, and raw materials in violation of the arms embargo.

Iraq is continuing to develop other platforms which most analysts believe probably are intended for delivering biological warfare agents. Immediately before the Gulf war, Baghdad attempted to convert a MiG-21 into an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to carry spray tanks capable of dispensing chemical or biological agents. UNSCOM assessed that the program to develop the spray system was successful, but the conversion of the MiG-21 was not. More recently, Baghdad has attempted to convert some of its L-29 jet trainer aircraft into UAVs that can be fitted with chemical and biological warfare (CBW) spray tanks, most likely a continuation of previous efforts with the MiG-21. Although much less sophisticated than ballistic missiles as a delivery platform, an aircraft—manned or unmanned—is the most efficient way to disseminate chemical and biological weapons over a large, distant area.

Iraq has been able to import dual-use, WMD-relevant equipment and material through procurements both within and outside the UN sanctions regime. Baghdad diverts some of the $10 billion worth of goods now entering Iraq every year for humanitarian needs to support the military and WMD programs instead. Iraq's growing ability to sell oil illicitly increases Baghdad's capabilities to finance its WMD programs. Over the last four years Baghdad's earnings from illicit oil sales have more than quadrupled to about $3 billion this year.

Even within the UN-authorized Oil-for-Food Program, Iraq does not hide that it wants to purchase military and WMD-related goods. For example, Baghdad diverted UN-approved trucks for military purposes and construction equipment to rehabilitate WMD-affiliated facilities, even though these items were approved only to help the civilian population.

UNMOVIC began screening contracts pursuant to UNSCR 1284 in December 1999 and since has identified more than 100 contracts containing dual-use items as defined in UNSCR 1051 that can be diverted into WMD programs. UNMOVIC also has requested that suppliers provide technical information on hundreds of other goods because of concerns about potential misuse of dual-use equipment. In many cases, Iraq has requested technology that clearly exceeds requirements for the stated commercial end-use when it easily could substitute items that could not be used for WMD.

[1] Mustard is a blister agent that causes medical casualties by blistering or burning exposed skin, eyes, lungs, and mucus membranes within hours of exposure. It is a persistent agent that can remain a hazard for days.

[2] Sarin, cyclosarin, and tabun are G-series nerve agents that can act within seconds of absorption through the skin or inhalation. These agents overstimulate muscles or glands with messages transmitted from nerves, causing convulsions and loss of consciousness. Tabun is persistent and can remain a hazard for days. Sarin and cyclosarin are not persistent and pose more of an inhalation hazard than a skin hazard.

[3] VX is a V-series nerve agent that is similar to but more advanced than G-series nerve agents in that it causes the same medical effects but is more toxic and much more persistent. Thus, it poses a far greater skin hazard than G-series agents. VX could be used for long-term contamination of territory.

[4] See footnote 5.

[5] Bacillus subtilis is commonly used as a simulant for B. anthracis.

[6] An infectious dose of anthrax is about 8,000 spores, or less than one-millionth of a gram in a non immuno-compromised person. Inhalation anthrax historically has been 100 percent fatal within five to seven days, although in recent cases aggressive medical treatment has reduced the fatality rate.

[7] Ricin can cause multiple organ failure within one or two days after inhalation.